spaces

Humanities Building

Chances are, when you think of heated philosophical debates, controversial architecture, or defining the spirit of the humanities, the words “administration building” are not the first things to pop into your head. However, all of these things feature prominently in the story of the Humanities Building at the University of New Mexico.

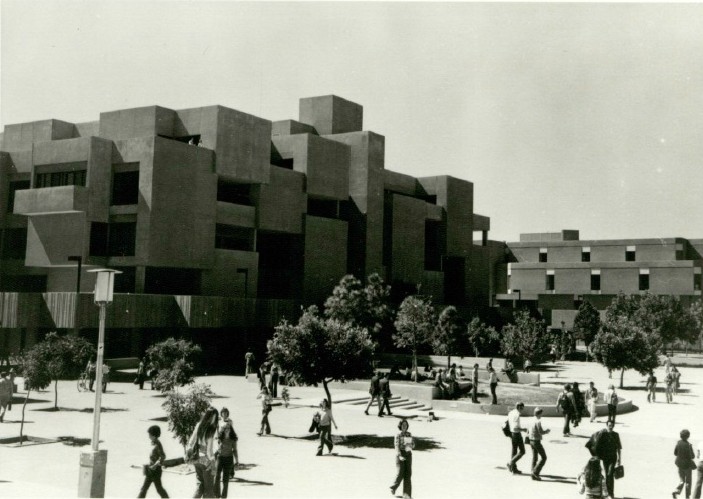

The physical form of the Humanites Building has not changed since its original construction in 1973, but its functions and the spaces around it on campus have changed dramatically in the years since.

Collaborative Design

As programs in the humanities at UNM continued to grow—namely, English, History, Philosophy, and the Honors program—there was an increasing need for more space. The Humanities Building was proposed in order to provide more classrooms, libaries, and office spaces for faculty members, teaching assistants, and graduate assistants. The construction of the Humanities Building was approved by the UNM Board of Educational Finance in June 1972.

In the initial stages of the design process, the department heads from English, Philosophy, and History worked together to describe what their disciplines needed and hoped to see in the new building.

Together, they drafted a 50+ page document titled “The Conception of a Humanities Building” in which they list practical details about the kinds of spaces and tools they needed, but they also devoted significant space in the document to a discussion how a humanities building should look and feel in order to complement the disciplinary goals of the departments it houses.

Sherman Smith sent this project approval letter to the heads of the departments that would be housed in the new Humanities Building, inviting their participation but also stressing the need for efficiency and speed in the building design and approval process.

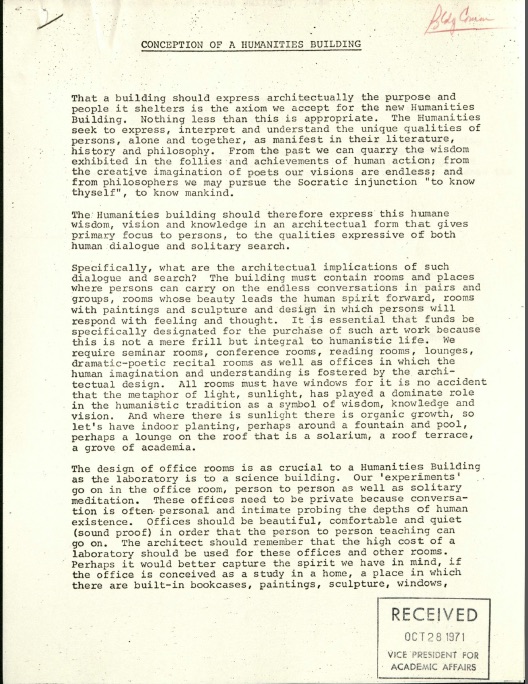

Leaders in English, History, and Philosophy wrote ‘The Conception of the Humanities Building’ in 1971, and on the very first page, they set the tone for the entire document with their desire for the building to ‘express…humane wisdom, vision and knowledge in an architectural form’

The document is surprisingly poetic and demonstrates an immediate engagement with not just the physical details of the building, but also with what the space will represent for the students and faculty members who use it. In the first paragraph, they begin the conversation about architecture by offering a definition of the humanities:

“That a building should express architecturally the purpose and people it shelters is the axiom we accept for the new Humanities building. Nothing less than this is appropriate. The Humanities seek to express, interpret and understand the unique qualities of persons, alone and together, as manifest in their literature, history and philosophy.”

They go on to craft a vision, both collaboratively and individually within departments, of a building that would reflect this eloquent and humanisitic vision. Among their group requests were:

- “rooms and places where persons can carry on the endless conversations in pairs and groups”

- “rooms whose beauty leads the human spirit forward”

- “rooms with paintings and sculpture and desing in which persons will respond with feeling and thought”

- “offices in which the human imagination and understanding is fostered by the architectural design”

They also made a particularly eloquent plea for natural lighting in the new building, writing:

“All rooms must have windows for it is no accident that the metaphor of light, sunlight, has played a dominate role in the humanistic tradition as a symbol of wisdom, knowledge and vision. And where there is sunlight there is organic growth, so let’s have indoor planting, perhaps around a fountain and pool, perhaps a lounge on the roof that is a solarium, a roof terrace, a grove of academia.”

The individual departments who contributed to the document each wrote extensive sections for themselves, expressing discipline-specific visions and needs.

The English department requested “a building that will be bright with light and light in feeling,” specifically requesting that it not be built in the “fortress architecture” style of other newly constructed buildings on campus—buildings they called “hulking bastions of solid or almost-solid concrete with disguised narrow slits rather than legitimate, honest-to-God windows for contact between outside and inside.” They also encouraged the architect to remember that the new building would be “a physical center, a symbol, a show place for the sun life that we all prize and advertise here in New Mexico,” demonstrating a desire to have the quality of the building match what, ideally, the experience of being at an institution of higher learning in the Southwest.

The Philosophy department requested that the space be designed “to encourage the careful reading and Socratic discussion between persons that form the heart of our work,” and the History department vehemently requested a building that “attracts rather than repells people.”

Controversy

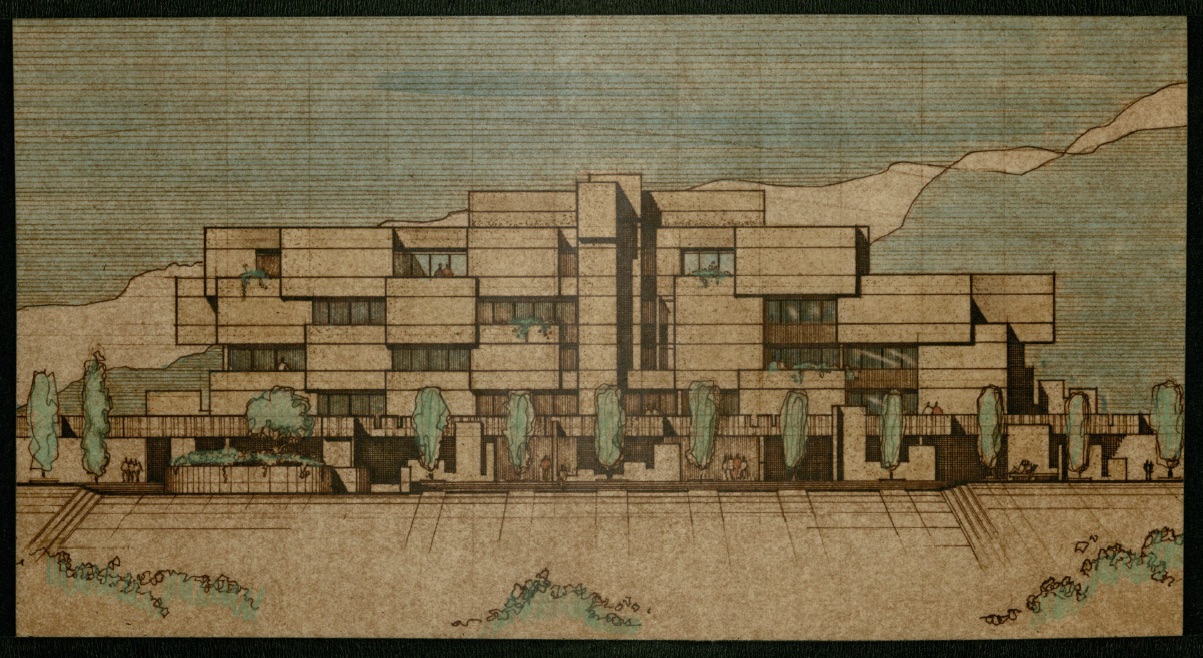

UNM hired W.C. Kruger & Associates as the architectural firm for the building project, and soon after the approval, Mr. Kruger sent drawings, such as the one shown below, for the proposed architecture out to the department leaders for comment.

This architectural drawing from Kruger focuses attention on the proposed new building but includes none of the surrounding buildings, which significantly alters viewer perception of the building and the space it would eventually occupy on campus.

Of course, as soon as the plans were released, they drew intense resistance. The proposed building was the opposite of everything that the departments had asked for—small windows, little natural light, tight spaces and corners, and a blocky, fortress-like appearance. The same people who originally composed “Conception of a Humanities Building” wrote letters to the architect and the UNM administration objecting to the design.

The History department put it best when they wrote:

“A massive cement blockhouse with tiny windows and partly concealed entrances may be suitable for a fall-out shelter or defense center in the event of enemy invasion, but is not in keeping with the function adn spirit of the humanities departments the new building is to house.”

However, in spite of the objections from department heads, the administration yielded to Kruger’s design vision, and the project moved ahead.

Construction

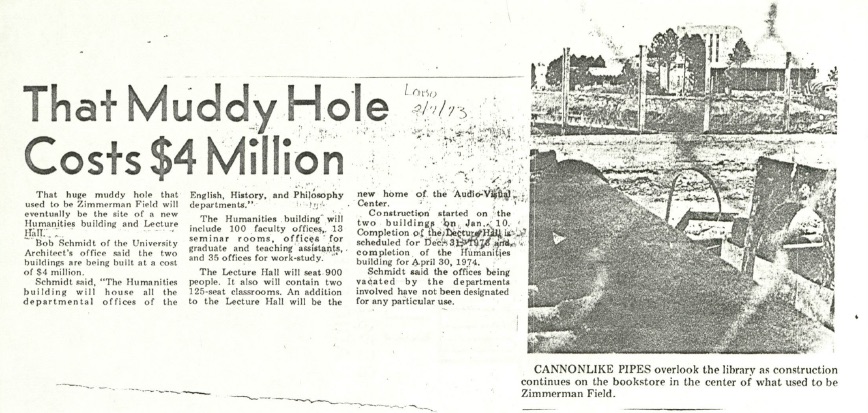

Construction on the building started in early 1973 with the excavation of Zimmerman Field, the open, grassy expanse behind the library.

On February 7, 1973, the Daily Lobo covered the ongoing Humanities Building construction project that had turned what was formerly a grassy field at the center of campus into a ‘muddy hole.’

The construction of the Humanities building, then, involved the simultaneous construction of what is now Smith Plaza.

Construction of the Humanities building and the plaza happened simultaneously, making the center of campus difficult to access.

The earliest version of Smith Plaza was constructed as a large, flat expanse of brick. As the picture shows, there were more trees but less green space where students can sit, like the current version of the plaza offers today.

When the building was finished in 1974, it overlooked a transformed campus space. Where there had once been only a field, now there was a large, open plaza, and many new departments in the humanities had a new permanent home. Though the building did not match their hopes or expectations, it did position them in an important part of campus, and the new plaza made the building more accessible, which would make it easier to encourage student engagement and presence in the building.

The newly bricked Smith Plaza brought much more foot traffic to the area behind Zimmerman, connecting two sides of campus.

Acclaim

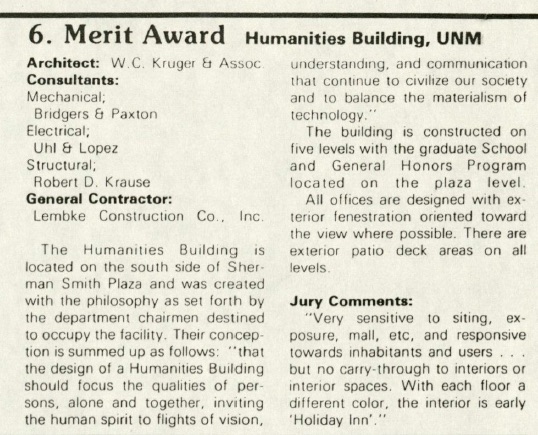

In 1977, the Humanities building won W.C. Kruger & Associates an Merit Award from The American Institute of Architects’ New Mexico Society of Architects. Jury comments for the award noted that the building was “sensitive to siting, exposure, mall, etc. and responsive toward inhabitants and users” and noted that the decision to design each floor using a different color made the building feel “early ‘Holiday Inn.’”

The article announcing Kruger’s architectural award quotes ‘The Conception of the Humanities Building’ in spite of the fact that the building did not at all match the vision or needs outlined in that document.

Over time, the function and occupancy of the Humanities building has shifted somewhat. As the programs it housed continued to grow, the rooms that had once been designed as seminar spaces and classrooms transitioned, for the most part, into being office space for faculty, staff, teaching assistants, and graduate assistants. The Honors program eventually became the Honors College and moved to its own space, and many of the departments housed there started holding more classes in Mitchell and Ortega Halls.

More significantly, especially since the 2018 renovation of Smith Plaza, the area around the Humanities building became a much more popular place for students to sit, converse, work, and walk. As a current graduate student who works in the Humanities building, I can personally attest to the fact that the people who work in the building regularly use Smith Plaza as a place to meet, work, and relax, and also as a way to give students directions to the building.

From this aerial view, you can see the building’s shaded exterior balconies as well as its windows, which are set deep into ‘tight spaces and corners’ of the block structure that the department heads so disliked because they limit the amount of light that enters the building.

The humanities are an important part of UNM’s culture and structure. All incoming first-year students, for instance, must take English 110 and/or 120, both of which are taught by English TAs whose offices are in the Humanities building. All instructors for these courses hold one-on-one conferences and office hours for students at least once per semester, meaning that nearly every student at UNM will spend time in the Humanities building during their first year on campus.

Because of this, the Humanities building occupies an important space, not only just geographically on campus, but also intellectually and experientially for the vast majority of the student population.

Bibliography

-

W. C. Kruger Architectural Drawings (unprocessed collection), stack 38, University of New Mexico Center for Southwest Research, University Libraries, University of New Mexico.

-

University of New Mexico, Dept. of Facility Planning architectural drawings, stack 20, drawer 3, University of New Mexico Center for Southwest Research.

-

University of New Mexico. Dept. of Facility Planning Records, 1889-, Collection UNMA 028, Box 54. Center for Southwest Research, University Libraries, University of New Mexico.